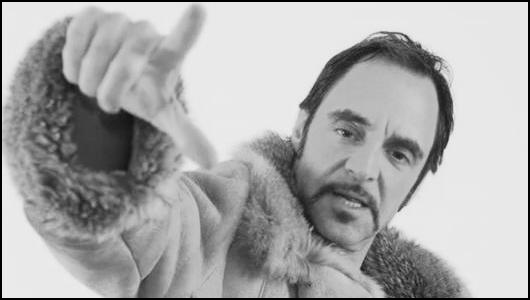

Rick Shapiro: King of Chaos

Rick Shapiro

It is hardly a surprise that even Rick Shapiro himself sometimes struggles to describe his own act. This is a stand up who has been variously compared to Richard Pryor, Philip Roth and Iggy Pop, a performer who combines bleak nihilism with heady surrealism, flights of frenetic verbal showmanship with dizzying rock star unpredictability. It is perfectly fitting that at one stage during a sprawling but engrossing conversation Shapiro speaks admiringly of a girl he once went out with who had a tattoo that said “Queen of Chaos”. If a humble stand up has the right to declare domain over anything, Shapiro surely has a worthy claim to the title “King of Chaos”.

Now based in LA, Shapiro first garnered attention in his native New York where he became a regular on the underground comedy circuit during the 90s. His freewheeling stream of consciousness monologues and splenetic rage fuelled rants have gained him a modest but devoted following and allowed him to become something of a cult hero, albeit a spectacularly self destructive one. Shapiro’s troubled past – struggling with alcohol and drug addiction and at his lowest ebb becoming a rent-boy to pay for his habit – is often fodder for his highly unpredictable, improvisational stand up shows. Four years ago a devastating car accident left Shapiro with complete amnesia, and it is only now, after years of painstaking rehabilitation, that Shapiro has been able to return to Edinburgh with his latest live show, the fittingly named Rebirth.

His speech slightly slurred and peppered with pauses, it’s clear that Shapiro is still in recovery. He admits that he’s still in pain and that doctors have told him that “it will take a while to realign my body” but Shapiro is also, understandably, keen not to dwell on his misfortune “I don’t want to bore you with that shit” he states calmly, and the interview hesitantly proceeds.

Given that the title Rebirth has clear symbolism, I put it to Shapiro that the show explores his painful return to reality after a traumatic break. As is so often the case with Shapiro, it is not that straight forward. “That’s a good idea for a show” Shapiro deadpans. “But it’s more like you’ll see that [recovery] happen. I work in a different way, so they’ll be rage, they’ll be goofiness but it’s like… I never plan it. I have no idea what kind of time bomb it’s gonna be.”

Another comedian using this explosive metaphor might be assumed to be exaggerating, but with Shapiro there is a sense here of real jeopardy. As a performer Shapiro can be unique, impulsive and painfully funny, but there is a genuine sense of risk involved. As he explains, it’s not just the audience who goes into his show unsure what they’ll be getting; the performer himself often has no idea what will come out of his mouth. “Oh I never know what I’m gonna do next. This is the first year I’m wondering. This year I might read from a book I wrote of strange essays [the fittingly titled Unfiltered], but I never know what I’m gonna do next, every show is different. I don’t want to say that it’s daunting but it is a pain and it’s fun. There how’s that?”

Although his style is highly distinctive, like Pryor, Doug Stanhope and that other great American misanthrope Bill Hicks, Shapiro is powered predominately by rage, with his act dominated by sprawling rants about everything from American politics to hollow capitalism to the mysteries of women. I wonder if to him stand up is therapeutic, a chance to vent his frustration at the world? Shapiro is as thoughtful and hesitant than ever. “I never call it therapy because I never feel like a million bucks, like all of a sudden I’m cured. I just feel like… wait let me think about your question…” He gathers his thoughts. “Sometimes if I’m lucky it feels like it has to be said, whether you’re talking about the banks or how a person wears their hair, it has to be said, whatever bothers you. It ought to be pointed out. I mean come on, there is so much bullshit in the world, and we’re so hypnotised! Therapy…If I bought a car and made a million bucks that would be therapeutic!”

The majority of stand ups describe performing as a kind of drug – after all, why would anyone risk their dignity by getting up on stage night after night in front of a crowd of strangers if it wasn’t causing some mischief with your brain chemistry? – but Shapiro, with all his experience of real hard drugs, is the most extreme manifestation of this phenomenon I have ever encountered. In New York, encouraged to start performing by an AA sponsor impressed by his impressions in a meeting, Shapiro would play obsessively night after night whether there was an audience or not. “I’d go on stage if there was no one in the room, if there was one person in the room” Shapiro recounts. “Comics would walk in and say I’m not playing this room, there’s no one here, and I’d say, ‘are you kidding? There’s two people in this room!’ If you can make two people laugh at 2am, then you can make a whole crowd laugh at 9… I’d have club owners tell me ‘go on a date, go home’, but I’d still do it, every single night.”

Given this obsession it is unsurprising that Shapiro has struggled to reconcile his vocation with a personal life. Off stage Shapiro has fought his demons – not just his addiction problems, but a chronic lack of self esteem – and seems to only just be beginning to feel that he deserves success and happiness. “I find my identity onstage, and offstage I’m trying to find it too… You can’t search for validation every night. Well you can, but offstage you have to find it too. I’ve been wandering around my whole life. I didn’t think I wanted an SUV and a girlfriend and a kid. I wanted to create all the time… I hate to use the words demons, but that self worth is something I have to work on all the time… [it’s] a big topic for me.”

Shapiro is the antithesis of the “career comedian.” Talking to him there is a refreshing lack of business savvy, and he is quick to admit that he’d rather “write some wimpy style stuff and make a million bucks but that’s not how I work.” His loner impulses meant that it took a long time for Shapiro to make friends in comedy. “I had a manager one time who called me up and said ‘you’re becoming an outsider, everybody likes you but…’ I was so ashamed of myself, of the life that I lived, the way I grew up… I would perform and run out of the room after I’d done, even if I killed. I was ashamed, I didn’t want to hang around with anyone, the whole time.” Slowly over the past decade Shapiro has been more involved with the television and film world, appearing in Louis CK’s short lived Lucky Louis, and more recently in brash teen flick Project X, as a violent drug dealer. Happily Shapiro seems to be enjoying these projects, hoping to pursue more acting roles in TV and film.

In a techno-savvy, commercially cynical society where we are bombarded with comedy as a consumer product from all sides, where the internet and television is saturated with the good, the bad and the bland of a crowded market place, Shapiro presents something refreshing and genuinely different. An act with ragged edges, with a foul but paradoxically poetic way with words, with no internal filter, no censor, no savvy publicity department encouraging him to dilute his raw material. Shapiro may be a sometimes difficult character, impulsive in the extreme, but when he’s on form he presents us with something sublime. When Shapiro states that “I’m done with this destructive [sic], I want to find new hobbies, instead of just drugs and sex,” you are left hoping that this will be the case, and that his “cool new shrink” and efficient manager can keep him on the path the recovery. After all, it would be a shame for such a unique talent to disappear.

Rick Shapiro’s Rebirth is at Assembly (George Square) until August 26th. For tickets, see: edfringe.com.